- Motion Realizing

- info@neuromove.it

THE ABILITY’ DECISION OF THE MOVEMENT

Keywords: decision making, voluntary movement, involuntary movement, motor drive, motor neurons, sensory organs, sports psychology, strategy, emotion, reading the motion, motor anticipation, motor memory, engram, learning.

INTRODUCTION

The human motricity is based on an unavoidable scientific law: each movement stems from a nerve impulse that allows the realization in more or less short time.

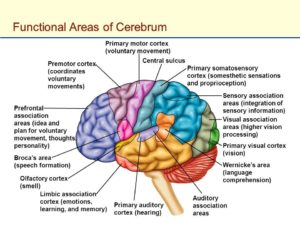

There are two types of movements: 1) voluntary ones, made with consciousness, which develop through the stimuli obtained from the sensory organs (eyes, nose, ears, tongue, skin, etc.) which, following the path of the spinal cord and going up the brainstem and cerebellum, they reach the cerebral cortex; the information deriving from the sensory organs is combined with that already present in the frontal association area of the brain, which come from the memory of past experiences, to make the decision of the motor act that must be performed. The new information is then sent, through the brain stem and spinal cord, to the affected muscles to produce movement. 2) Involuntary (or reflex) movements are also produced through the stimulus of the sense organs but, once passed through the spinal cord, they are resolved at the level of the brainstem and cerebellum, without reaching the cerebral cortex and, therefore , without being brought to consciousness. Precisely for this reason the movement that is produced is immediate.

LEARNING, AUTOMATION AND MOVEMENT OF PERFECTION

It goes without saying that any movement arises as a voluntary one. When, for example, in sport, we learn a new technical gesture, we proceed by trial and error and thinking (conscience) about all the details that characterize it (kicking the ball: running, stopping the support foot at the right distance, kicking with the correct position foot, perception of the trajectory, etc.). The technique is based on voluntary partial movements, in which excessive attentional control makes them rigid, awkward, disharmonious and tiring. The central nervous system of a beginner does not know the correct sequence of movements that generate the specific technical gesture, failing to achieve the contraction and decontraction of the musculature in the appropriate measure and times, activating more muscles than would be necessary (the agonist muscle produces an excessive force that the antagonist must oppose to restrain it).

Once you become more experienced it will be possible to create a certain movement in a more automatic and casual way, no longer thinking about the fundamental characteristics that determine it, but focusing on other details that perfect its execution. The movements of daily life, for example, are 80% automatic (getting dressed, brushing your teeth, drinking a glass of water, writing, driving, etc.), precisely because they have been performed thousands of times. According to Schinner, the motor pattern of an act of medium-high complexity is stably structured after about 3000 repetitions. From this point on we start talking about motor learning, described over the years by many authors and scholars. Tolman talks about M.A.M. (Motor Learning Maps) as cognitive maps, models whose assimilation takes place through various processes all tending to the acquisition of experience, easily associated with motor memory and motor engram. The M.A.M. are developed in 4 phases:

- Project – the student will create a mental model based on the information in its possession: memories, explanations, demonstrations, etc.

- execution – test the movement becoming aware of the positive or negative result achieved

- Adaptation – make those changes that the experience and / or the teacher suggested the

- Consolidation – run a good number of repetitions to perfect the project and create a neural structure, the movement pattern.

All these functions are possible thanks to a system called, precisely, motor memory, which consists of circuits formed by many neurons connected together, each of which controls a partial phase of a movement. Whenever we learn a motion forms a new circuit, which remains imprinted in this area of the brain (memory) and will be triggered whenever a nerve impulse will require that kind of movement. This explains, among other things, because certain similar movements interfere with each other: “while throwing me out the baseball joke tennis”or “while running an upside-down comes the fall of judo”. In fact, nerve impulses tend to follow the old “tracked”, Which correct the path becomes very difficult, but possible if you have a large motor patterns memory, as it allows easier learning of new movements.

The area of the brain that is activated in motor memorization is the temporal area, especially that of the right hemisphere. But, in general, the movement and also its memorization are composed of many factors, which activate different brain areas involved in this procedure. In fact, the hippocampus area (the innermost part of the brain) records spatial memory; also in the innermost area of the brain, in an area called the amygdala, the recovery of emotional memory occurs; the verbal one is located in the frontal cortex of the left hemisphere; the associated space-time (the where and when) in the left and right frontal cortex; visual memory is located at the level of the occipital lobe; that of sounds and melodies in the right occipital lobe.

THE ACTIVITY’ BRAIN IN SPORT

In competition situations, athletes' brain activity is at the highest levels; he is extremely tense, attentive and focused on his own movements (gymnastics, diving, skating, etc.) or those of his opponents (tennis, volleyball, combat sports, etc.). In these situations it is clear how the athlete's experience plays a fundamental role in the management of all the circumstances that occur, putting in place a cognitive activity in order to perform a coordinated and appropriate movement and a rapid response resulting from a decision. . It is therefore intended to read and analyze the situation that arises at a given moment and compare it with one's own past experiences (frontal association area – motor memory), looking for a strategy for responding to the movement.

In this state of high brain activity, the athlete displays in advance (remembering a picture) movement that is trying to perform, creating a sort of gesture of the final test. Returning to the learning phase, in accordance with the “theory of reinforcement” of Schinner, the individual learns when the response gives him a reward (you need to check regularly the progress). It is clear, therefore, that the athlete devoid of experience necessary to obtain the “gratification”, the result of endless hours of practice essential for learning the technical gesture, cannot have an evident and clear memory of an image to implement the correct movement. The accumulation of experience in an athlete allows him, through various attempts, to spontaneously develop an increasingly precise movement.

However, in competitions at the highest levels, all athletes have a very high level of experience that allows them to carry out technical gestures with ease. In sports where it is necessary to react in a very short time to the movements of an opponent, the reading of the situation becomes very important and, again, experience allows us to grasp even the most imperceptible of details. Imagining a situation in which two athletes, with the same motor skills and amount of experience, had to be compared, who would win? What factors would be determining for which one prevails over the other?

emotionality’ AND EXPRESSION OF YOURSELF

Often athletes are judged on their technical / athletic abilities that they are able to field during a competition, without wondering why a particular athlete has certain skills. Speaking of conditional skills (strength, endurance, speed, flexibility and balance) we can refer to genetics, if we think of the pure aspect (without specific training) of each of them present in the athlete's DNA. Considering, however, the psychological aspect, which strategies are implemented to win or how you react to a given situation, we cannot dwell on the characteristics “scientific”, Measured by tests or based on sports scores, and even brain activity, more difficult but possible response.

Every athlete, as a human being, is endowed with an emotional sphere which, together with thought, plays a fundamental role in the existence of an individual. Unlike the rational sphere, which acts on the basis of objective evidence, the emotional sphere is guided by immediate intuition, manifests itself in a much shorter time than the first and in an unconscious way. Each of us will have happened to discard an opponent, parry a blow or perform a movement without knowing how to do it. Well, also in the reading of a game situation, of an opponent's movement and even in the methodology and in the learning modality, there are aspects of the personal emotional sphere that have a decisive influence on the decision-making abilities and brain activity.

Returning to the competition and the reading of the competition situation, being an athlete, understood as an individual, different from any other, he will have different and, it can be said, unique interpretation skills, which depend on many factors, including the personal emotional sphere. and the emotional state in that particular situation. The athlete who emotionally tends to suffer a situation will have the defense as a first reaction to an opponent's attack; the one who, on the other hand, proves to be more abusive, will conceive the opponent's attack itself as a direct opportunity to counterattack. This does not mean that athletes “aggressive” always prevail over the other, but is meant to highlight how to understand and manage their emotions, to find an opponent and be able to relate the time of the competition, can be the key to solving the race situation to their advantage.

CONCLUSION

The motor capacity that comes closest to this concept is called transformation (or motor anticipation), ie the capacity that allows us to vary an action taking place as a function of’ developments in these areas. However, this important ability, even if well-trained, is not by itself able to make us obtain the absolute control of an adversary, because its realization always occurs in response to his movements. To understand and interpret the movements of an opponent and the situation that will occur as a result, you need to act in advance, have the ability to look not only through the eyes, but also through the emotions.

In “Gorin no sho” il Samurai Miyamoto Musashi (1584-1645) parla di “two ways of looking, kan and ken”, Explaining how to observe an opponent. It distinguishes the '”eye ken”, Which recognizes the opponent's figure as is reflected in the retina of the eye, and the '”eye kan”, which reads inside the opponent's soul. Obviously, this concept refers to philosophical aspects very distant from us in terms of age and culture, the opponent we are talking about was an enemy to be eliminated and prevailing over it was a matter of life or death. Although Western sport is based on a different culture, this concept is interpreted as victory or defeat, so prevailing over an opponent has remained, in the same way, the primary objective. Here then we can draw from the philosophy of oriental martial arts the ability to emotionally relate to an opponent in order to read his movements to create a situation to our advantage; or even learning to manage one's emotions according to the match situation, for sports where there is no such direct relationship with the opponent.

In Kendo (Japanese fencing), for example, the techniques are carried out in very short times and spaces, where in order to be ready for a sudden attack or to strike without hesitation at the right moment, two factors become relevant: the first is how to perform the technique appropriately, and the second is the practitioner's spiritual (emotional) attitude. Why do young people in full strength fail to hit older teachers with a lot of experience? Why is it the elderly teachers who strike the young? Perhaps it can be said that it depends on the physiological process of maturation which is part of the development of the human being and which goes far beyond just motor skills. In western sports physicality and biological age play a much more important role than in martial arts, but if we were able to also consider a development of the emotional abilities of an athlete, as a sportsman but above all as a person, sport and competition they would benefit from it.

At the moment the NEUROMOVE methodology is working to study the emotional sphere of its students, thus bringing new goals in human motion research.

REFERENCES

- “The nervous system and the movement” – www.libero.it

- “KENDO – Introduction to Practice” – Hiroshi Kanzaki

- “The system PSI.CO.M” – Fùndacion Carmelo Pittera

- “Human anatomy” – Martini, Timmons

- “Gorin no Sho” – Miyamoto Musashi

AUTHOR

Giacomo Pezzo